Turn Chaotic Reviews Into Clear Decisions

The write-then-meet framework for running great technical reviews

Welcome back to Path to Staff! We’re continuing our series on Mastering Communication.

Today, I want to share a framework that has completely changed how I run technical reviews —meetings where senior engineers come together to evaluate a decision and align on a direction.

A 1-minute story:

Early on in my career, I scheduled a technical review for a design I had been working on for weeks. I was proud of it, and I wanted feedback from smart people. So I invited eight of them: engineers from adjacent teams, a PM, a tech lead. More eyes, better feedback, right?

The meeting started. I pulled up my document and began walking through it.

People started reading along. Then the questions came. Then the critiques. Someone in the back raised a concern about my approach in section two. Someone else wanted to revisit the problem statement entirely. A third person was still on page one and asking me to slow down.

Given that I only budgeted 30 mins, we quickly ran out of time. And guess what: No decision was made. I left with a pile of conflicting feedback and no idea what to do next.

I was disappointed, both with how the review went and myself for not planning properly. The worst part was feeling that I had wasted the time of eight busy people who probably had better things to do that hour. Should I have sent the doc async instead? Should I have kept the meeting shorter? Should I have invited fewer people?

After trial and error over a decade, I realized the trick to these reviews isn’t whether to write or meet.

The question is how to sequence them.

For any technical decision that matters, you almost always need both. The key is doing them in the right order, with the right structure in between.

Let me walk you through how I think about this.

The Framework: Write First, Meet Second

The best technical reviews that I’ve participated in, both as a presenter and as a reviewer, follow a consistent pattern:

Write a focused document: This should lay out the problem, the options, and your recommendation. Keep it to three or four pages. Any longer and people won’t read it. Any shorter and you probably don’t need a meeting at all.

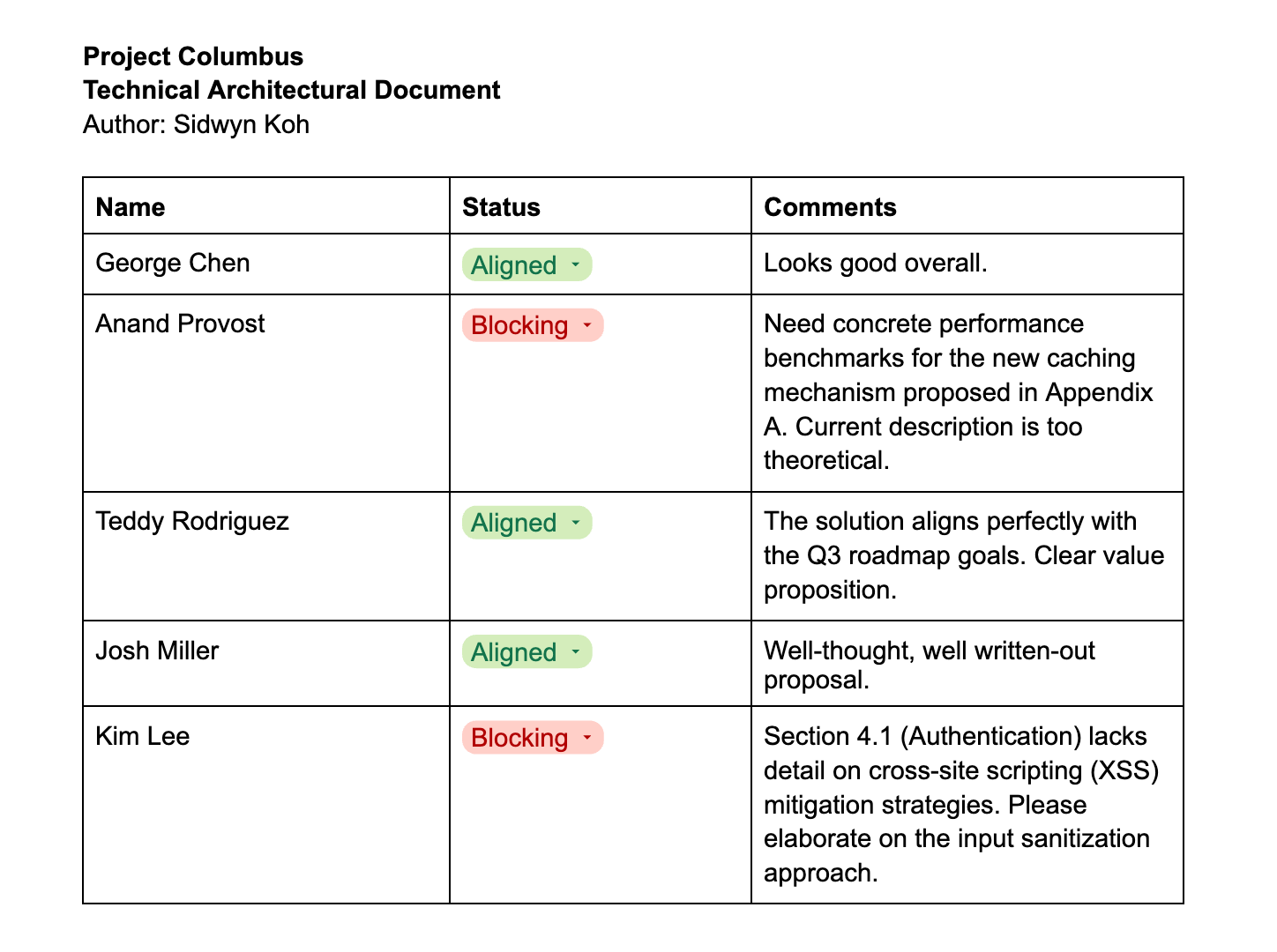

Add an alignment table at the top where reviewers can signal their stance before the meeting. Something simple: their name, whether they agree or have concerns, and any key questions. This gives you a read on the room before you even walk in.

Send it as a pre-read one to two days before the meeting. This timing is important, and I’ll explain why in a moment.

Use the meeting to resolve, and not to review. If everyone has read the doc and left comments, you don’t need to present anything. Go straight to the open questions. I typically like to lead in by saying, “Alright, since everyone has had a chance to read this document ahead of time, we will go over a few of these comments in the doc.” Use the time to drive toward a decision.

Just implementing these four steps will already do wonders for your review.

Why Timing Matters

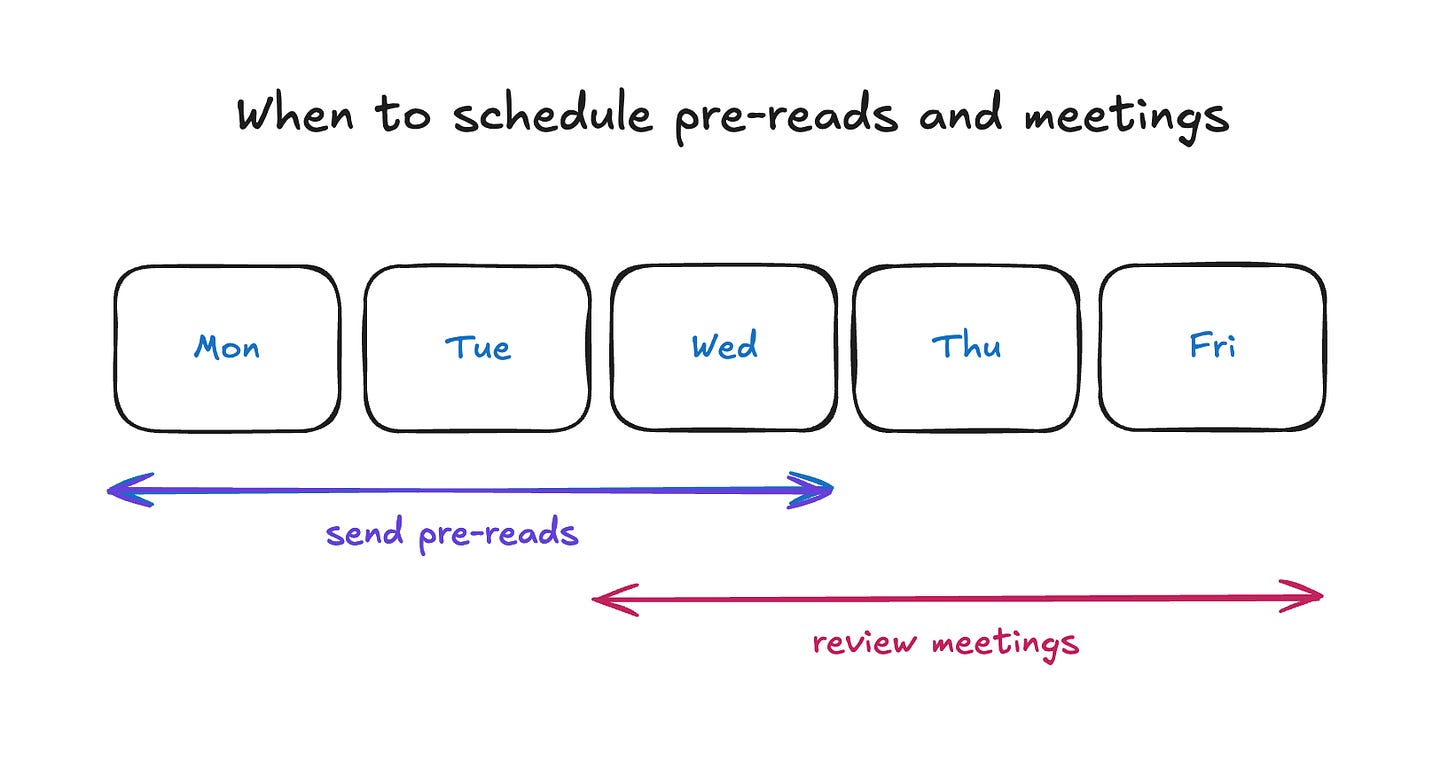

I mentioned that one to two days is the sweet spot for sending out a pre-read. Here’s why.

If you send it too late, people won’t have time to read it. They’ll show up cold, and you’ll end up doing what I did in that first disastrous meeting: reading the doc together in real time, fielding questions as they pop up, running out of time before anything gets decided.

If you send it too early, people will forget. They’ll skim it on Monday, the meeting lands on Friday, and by then they’ve lost all context. You’ll spend the first ten minutes re-orienting everyone anyway. I’ve done this too many times to count.

One to two days gives people enough time to read and comment, without so much time that it falls off their radar. I’ve found this window works well even for busy reviewers. This means your ideal review day should not be Monday or Tuesday, since folks are not going to be remembering what you sent them on Friday.

What Makes This Fail

Even with this framework, things can go wrong. Here are a few failure modes I’ve seen:

The doc is too sparse. Make sure your doc is substantive enough that it invites real feedback. No one wants to be the first to leave a critical comment on something that looks half-baked.

The reviewers are too senior. This one surprised me. If you invite people who are two or three levels above you, they often won’t comment ahead of time. They’ll wait for the meeting to weigh in. The best reviewers are usually plus or minus one level from you. Close enough to the work to engage meaningfully, but senior enough to offer useful perspective. This is what’s worked well for me.

Too many people in the room. The more people you invite, the harder it is to drive toward a decision. Everyone has something to say, and the conversation spirals. Keep the invite list tight. If someone just needs to stay informed, send them the doc afterward. Don’t invite them to the meeting.

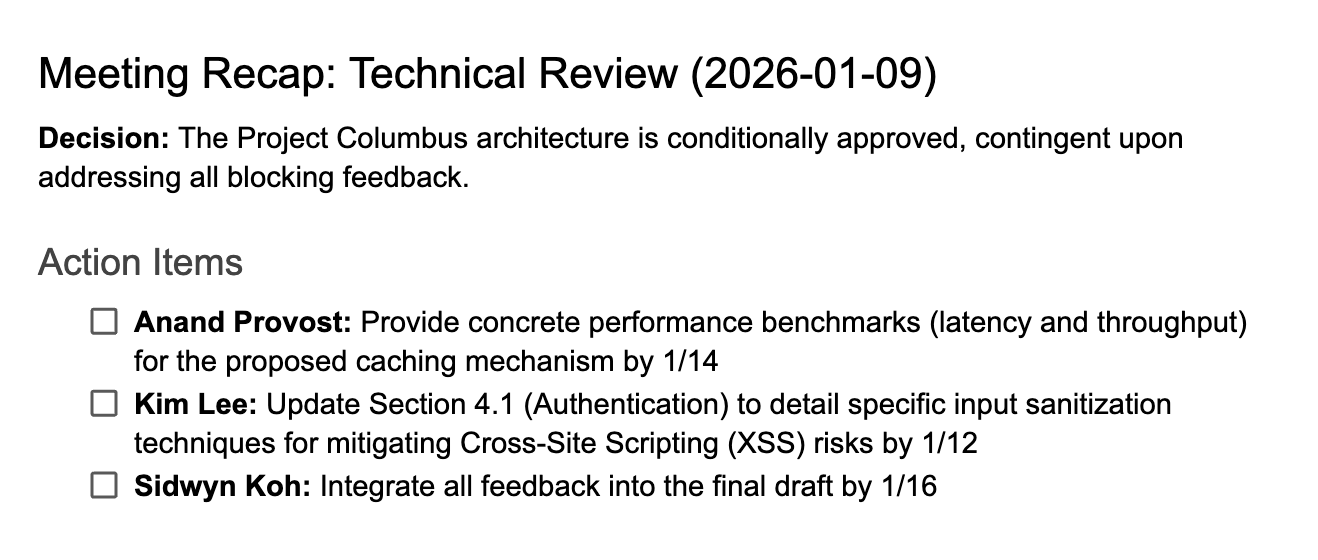

Forgetting to recap decisions and action items. After the meeting, you need to make sure you recap the action items from the decision meeting. This doesn’t have to be complicated and can be as simple as this:

TLDR:

That’s it! Here’s the quick summary so you can stop running reviews that waste everyone’s time:

Write, then meet. To make meaningful decisions, you first need to jot down your ideas on paper. Write first, meet second, and decide together.

Write a 3-4 page doc with a clear recommendation and add a comment table at the top for reviewers to signal their stance.

Send it 1-2 days before the meeting. Not too early, not too late. This gives folks enough time to understand what you’re asking them to weigh in on.

Use the meeting to resolve open questions, not to walk through the doc.

Watch out for failure modes: docs that are too sparse, reviewers who are too senior, and meetings with too many people, forgetting to recap.

One more thing: this framework applies to bigger decisions, the kind that need multiple reviewers and a formal meeting. For simpler decisions, a quick call or Slack thread is often the right move. Knowing when a decision is “big enough” for this process versus when you should just hop on a quick sync is nuanced, and I’ll write more about that distinction in a future post.

If you enjoyed this, check out the other posts in the Mastering Communication series: Part 1: How to Deliver Value Every Time and Part 2: Make Hard Choices Easy to Understand.

Really solid advice in this article, Sidwyn. I loved the images to show what an example looks like too.

Quick question, when you ask for the pre-read async, how do you approach it when people don't pre-read anyway?