Death of the Coding Machine: The Archetypes Replacing It You Need to Know

New Staff Archetypes in the Age of AI

Welcome back to Path to Staff! We recently hit 6k subscribers! Thank you for supporting this newsletter.

If you like shorter-form content, I have also been recently writing more over on Threads and X, on top of LinkedIn, so be sure to follow me there.

Today, we have a guest post from Michael Novati, co-founder of Formation.dev.

Michael was a Principal Engineer (E7) at Meta. He’s also a Coding Machine, which is a Meta senior archetype that was modeled after Michael. What is a coding machine? A coding machine is someone who has exceptionally high output and technical impact. They move fast, unblock teams and perform massive-scale refactoring.

With the rise of AI driving the majority of code creation in today’s world, Michael shares his thoughts about the Coding Machine archetype, and what he thinks the three new coding machine archetypes.

Without further ado, here’s Michael.

For most of the last decade, the path to Staff Engineer for high-output engineers was simple.

You wrote more code than your peers. You shipped faster. You absorbed complexity and turned it into merged pull requests at a pace that made you obviously, measurably valuable.

The archetype had a name — the Coding Machine — and it worked because the underlying economics made sense: code was the bottleneck, and anyone who could produce more of it was worth promoting.

I lived this. At Meta, I was the company’s top code committer for a stretch.

I made Staff engineer by 25 by being prolific in a way that was hard to argue with. The system rewarded output, so I optimized for output. It wasn’t complicated.

Then AI coding tools went mainstream, and the economics changed.

The Collapse

When these tools went mainstream: output increased, and quality decreased. It’s not because AI writes bad code (it often writes fine code), but because the systems around code review were built for human-speed generation.

Think about this: when you 10x the rate at which code enters a codebase, you don’t automatically 10x the rate at which anyone can verify it.

The numbers are stark. PRs are now roughly 18% larger on average as AI adoption increases. Incidents per PR are up about 24%. Change failure rates have climbed around 30%.

The bottleneck moved. We went from “not enough code” to “not enough judgment,” and most organizations are still staffed for the old constraint. Raw output became cheap and the Coding Machine archetype collapsed.

A mid-level engineer with Copilot can now produce implementation volume that would have been exceptional in 2015. The thing that used to separate the best ICs from everyone else — sheer generative capacity — is now available to anyone willing to learn the tools.

From Execution to Judgment

The old Coding Machine was optimized for execution.

The new version is optimized for judgment.

Anthropic published research on how their engineers use AI, and one finding stood out: people consistently avoid delegating tasks that require “high-level thinking, organizational context, or taste.” They hand off implementation, refactoring, test generation — basically anything verifiable. But decisions about what to build and whether the output is actually good? Those stay human.

The Coding Machine used to be the person who could hold the most context and type the fastest. The evolved version of the Coding Machine is now the person who can evaluate the most options and choose the best one.

With AI, engineers now generate ten plausible implementations in the time it used to take to write one. But someone has to decide which one ships. The judgment skill here is now what matters.

As the Warp CEO put it: “This was supposed to be the year AI replaced developers, but it wasn’t even close. What actually happened is developers became orchestrators of AI agents — a role that demands the same technical judgment, critical thinking, and adaptability they’ve always had.”

Three Evolutions

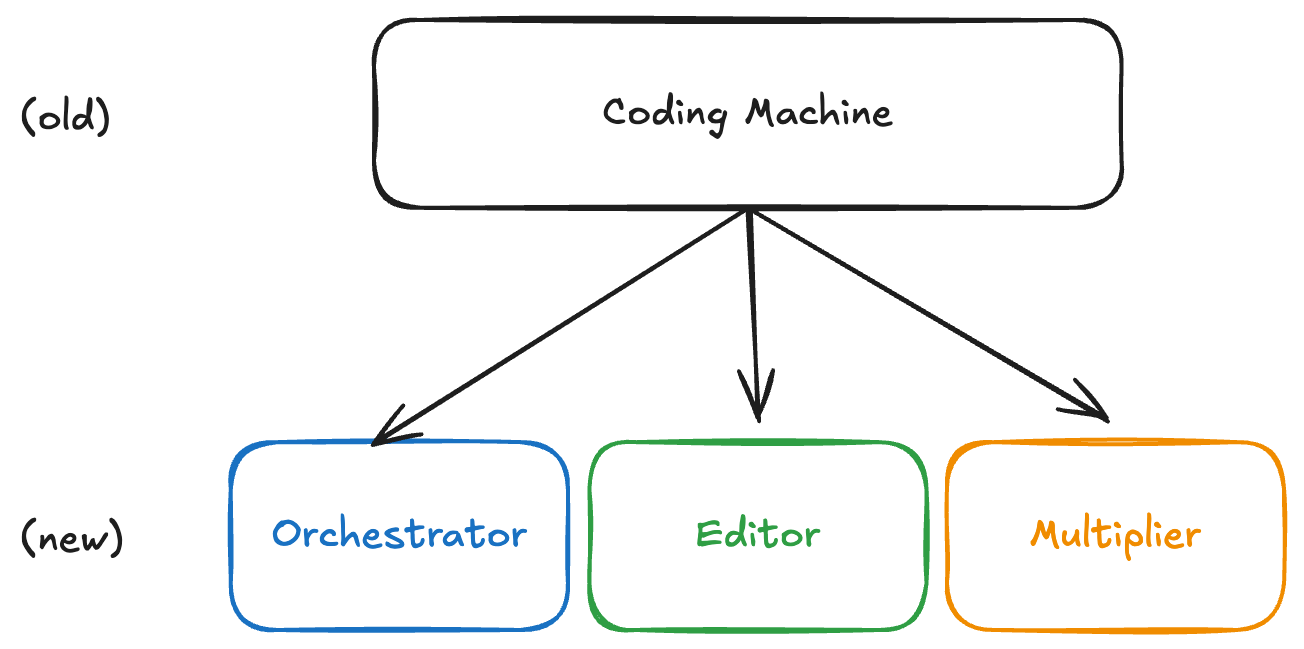

With that said, if the old archetype was Coding Machine (Execution), the new archetypes are what happens when you apply that same intensity to judgment.

These three patterns are emerging.

The Orchestrator

The Orchestrator designs work instead of doing it. They take a vague goal and turn it into a structured task graph that AI agents can execute in parallel.

They decide what gets decomposed, where the verification gates go, and how the pieces recombine into something coherent. This is basically architecture applied to the process of building, not just the artifact being built.

The failure mode is “agent spamming”: pointing AI at everything and calling the resulting chaos velocity. Don’t do this.

The Editor

The Editor curates output instead of generating it. Addy Osmani framed it well: “The human reviewer’s role becomes more like an editor or architect.”

This means treating AI output the way a newspaper editor treats wire copy. It arrived fast, it’s probably mostly fine, but someone has to catch the subtle errors and ensure it fits.

The best Editors develop institutional taste: they know things about the codebase that aren’t written down, and they can look at technically-correct code and say “this will break us in six months.”

The failure mode in this case is becoming a bottleneck who blocks everything. Be rigid about what should enter the codebase, but don’t be overly rigid where you block all PRs for the sake of doing so.

The Multiplier

The Multiplier is measured by what they enable rather than what they ship. Google’s DORA research called AI “a mirror and a multiplier”. In cohesive organizations, it amplifies strength. In fragmented ones, it amplifies dysfunction.

The Multiplier builds the infrastructure that makes AI useful across teams: shared workflows, evaluation frameworks, guardrails that prevent common failures.

The failure mode is what I’d call “influencer engineering”: giving talks about best practices without shipping the tooling that makes them easy. Don’t be an influencer who masquerades as a multiplier.

How This Plays Out In Companies…

Formation

I run Formation, an interview prep platform for experienced engineers. At Formation, we see these archetypes emerging in how we approach AI-assisted work.

I’ve seen that the ones who advance fastest aren’t generating more code. They’re the ones who develop good judgment earlier than their peers expect.

They learn to orchestrate before they’re asked to, edit before they’re senior enough to review, multiply before they have the title that usually comes with it. And of course, they take initiative by default. Nothing is someone else’s problem.

Meta

At Meta, the pattern is similar but at scale. The engineers getting promoted to Staff+ are increasingly those who can manage the output of AI-augmented teams without becoming bottlenecks themselves.

The Coding Machine energy is still there. It’s pointed at verification and leverage instead of raw generation. They build the systems that let dozens of engineers (human and AI) ship coherently.

What’s interesting to me is that AI naturally elevates the values Meta was built on. Move fast. Be bold. Focus on impact. Nothing is someone else’s problem. These used to be cultural aspirations that some engineers embodied and others didn’t. Now these are all table stakes.

The Real Shift In Skills

A lot of engineers are struggling because they’re still optimizing for output in a world that now rewards judgment. They’re shipping more code than ever—but getting less credit for it.

The reason is that the scoreboard has changed. Volume is now table stakes.

The Coding Machine is “dead” because the game moved on.

There’s one piece of good news though. The skills that made someone great at it (deep focus, pattern recognition, and comfort with complexity) still matter.

These skills just need a new target: design the system, curate the output, or enable other people to move faster.

What Route I’d Choose

Now, what route would I choose if I were coming up as a Coding Machine today?

I’d be an Editor (curating output). Same speed, same taste, same pattern-matching instincts, but applied differently.

Instead of writing more code than anyone else, I’d be ingesting 10x the raw output and instantly calling out the obscure edge cases. Calling out the bugs the AI didn’t consider, and the architectural decisions that look fine locally but rot the system over time.

I’d be adjusting the AI infrastructure and review processes to catch these things automatically going forward. It’s like code reviewing the work of dozens of engineers, except those engineers are machines I have more control over and more predictability around.

The throughput orientation survives. The target changes.

The Coding Machine has evolved.

Whether you evolve with it is up to you.

TLDR

AI made code volume cheap . My edge now is judgment (what should actually ship?).

As PRs get bigger and failure rates rise, the bottleneck shifts from writing to reviewing + verifying.

I see three archetypes emerging:

Orchestrator (decompose + add gates)

Editor (curate with taste)

Multiplier (build guardrails/workflows)

The people leveling up fastest optimize for correctness, coherence, and leverage — not raw output.

If I were coming up today, I’d choose being an Editor: ingest 10x output, catch subtle risks, and improve the systems that prevent them.

A big thanks Michael Novati for guest posting today. If you’re interested in more of his writing, check him out on LinkedIn.

A great read as usual, Michael and Sidwyn! I agree with the new archetypes you mentioned in the post-AI world. What I don't fully understand is that the framing makes it seem like you didn't have these skills in the pre-AI world and could just become a Staff Engineer by 10x'ing your execution output at a mid-level engineer skill/knowledge set. Was that actually the case for you, or am I misunderstanding?

Holistically, my take is that while everyone can output more code now, the baseline expectations of each level are still fundamentally the same, but we've now raised the floor at every level for how much of that you're expected to produce.